By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

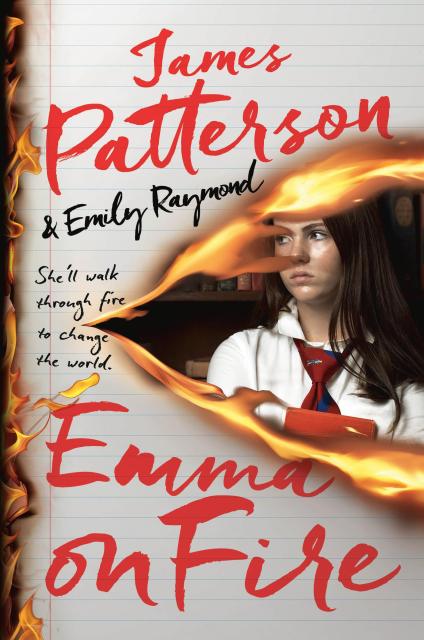

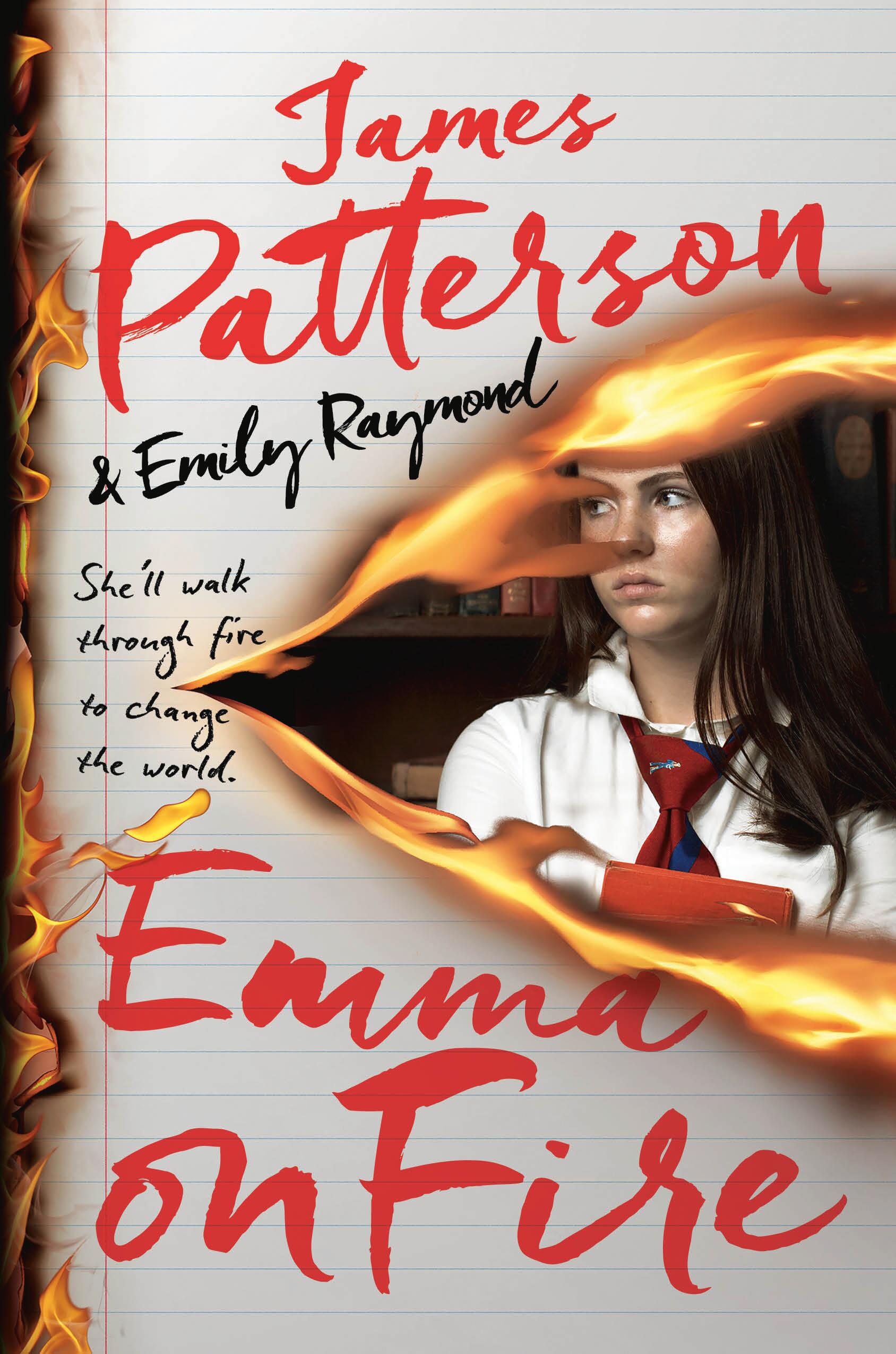

Emma on Fire

A Thriller

Contributors

By Emily Raymond

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Aug 19, 2025

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9781538758717

Price

$35.00Price

$45.00 CADFormat

Format:

Buy from Other Retailers:

An urgent, emotional thriller: “Dramatic…explores the power of grief…that through loss there can be hope for the future” (Library Journal).

Everyone at Ridgemont Academy knows what to expect from Emma Caroline Blake.

Perfect grades. Perfect record. Perfect life.

Then she stands up in class and commits an act so shocking her reputation will never recover.

And that’s exactly what Emma wants.

In a world where the path forward is uncertain, expectation is the enemy. Emma on Fire is the unforgettable story of one brave young woman—and her decision to live life as if everyone’s future depends on it.

Because it does.

-

"Dramatic...explores the power of grief...that through loss there can be hope for the future."Library Journal

What's Inside

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

•••

Chapter 1

Four days before the fire

EMMA CAROLINE BLAKE decides to drop the bomb in third-period AP English.

It’s not a literal bomb, obviously. It won’t blow up any buildings; it’s not even going to knock over a desk. But it will, she hopes, destroy something, which is the smug complacency of literally everyone here at Ridgemont Academy, an extremely elite, extremely expensive prep school in the foothills of New Hampshire’s White Mountains.

On this beautiful spring day, six weeks before graduation, Emma is completing the first homework she’s done this semester—unless you count reading, which Emma doesn’t. Reading isn’t work; reading is escape. It’s an essay that Emma spent an entire week researching, then all night writing in a Monster Energy–powered blur.

It’s also the first time in a long time that Emma has felt like something that was happening at Ridgemont Academy actually mattered. She couldn’t participate in the excitement of the lacrosse team (once again) being on a winning streak, or the daughters of the one-percenters giggling behind their phones while they snapped pics of the “blue-collar hot” boy who had been hired to muck out stalls.

Mr. Montgomery, their young, bookishly handsome teacher, gave them the assignment as a break. (A break at Ridgemont doesn’t mean no homework; it means slightly easier homework.) He told them that because everyone had written such excellent critical essays on Anna Karenina, they deserved to have some fun with a descriptive essay.

Fun didn’t really seem like the right word, if you asked Emma, but since she hadn’t written an Anna Karenina essay at all, she felt like it was best to keep her mouth shut.

“Describe your socks,” Mr. Montgomery said, “or your first car, or the way the sun sets over the ocean, or what it feels like to be caught in a rainstorm. Use your personal experience! Be creative! Don’t forget specific, concrete details and descriptive language!” He seemed so excited, talking about it. Like he couldn’t wait to see what they’d come up with.

Emma considered fulfilling the essay requirements by using descriptive language and concrete details about the videos that her roommate, Olivia, uploaded to her OnlyFans account, but she ultimately decided that yet another naked teenage girl on the Internet wasn’t really the shake-up that Ridgemont needed.

Now, sitting in his class, feeling the warm breeze like sandpaper on her skin, Emma feels certain Mr. Montgomery is not going to like what she came up with. Which is totally fine with her. In fact, it’s kind of the point.

At the front of the room, nerdy, yellow-haired Rhaina Johnson is reading about her antique French horn and how she feels when trying to play Richard Strauss’s Alpine Symphony on it. The rest of the class is totally distracted, although a few students giggle when Rhaina describes the experience as “ecstatic.”

“It’s probably the closest she’ll ever get to an orgasm, amiright?”

Emma overhears Nathaniel “Chewy” Ballantine whispering this to same-named Nathaniel “Nate” Gourdet. Nate snorts appreciatively, not noticing Emma glaring at them. Not that he’d care if he did. Once upon a time, a scathing glance from Emma Blake would have meant something. But all kinds of things have changed.

Not one of them, Emma would note, for the better.

When Rhaina finishes her essay, Mr. Montgomery leads the class in a round of applause, increasing his in volume and enthusiasm to get his students to follow suit.

“All right,” he says, “who’s up next?” He looks hopefully around the room.

Usually half a dozen hands would shoot up. But no one’s thinking about school for once; everyone just wants to be outside in the golden April sunshine.

Finally, Emma lifts her hand. Mr. Montgomery looks surprised.

“Emma?” he asks. “Are we participating today?” He sounds so hopeful, so relieved. It’s been months since she’s volunteered for anything.

She imagines his own descriptive essay, the one he’ll submit with his doctorate application, about how he really made a difference in this one girl’s life. This girl who had obviously been hurting for so long. This girl who just needed the spiritual cleansing of a descriptive essay to restore all of her emotional balance and return her to her former glory.

“We are,” Emma says.

Mr. Montgomery smiles. “I’m so glad to hear it.”

Pretty soon he won’t be. Pretty soon he’ll be worried about whether he’s even going to be allowed to continue teaching at Ridgemont, let alone getting his doctorate in being intuitively connected to his students.

Emma picks up her essay and walks to the front of the room. When she turns to face the class, they look a little more interested than they did when Rhaina was reading. And they should. Because what she’s got is better than French horns and outdated composers. What she’s got will get a full-page spread in the yearbook, along with the head- ing “Local Tragedy Highlights Global Problems.”

Chewy blows her a kiss from the back row, and Emma rolls her eyes at him. He can’t help himself, he’ll flirt with a brick wall.

She stands up straighter. Clears her throat. “Trigger warning, guys,” she says. “My topic today”—she offers them a quick, false smile—“is self-immolation.”

•••

Chapter 2

SHE HEARS MR. MONTGOMERY give a quick, sharp inhale. Chewy goes, “Self-immowhat?”

Emma makes a mostly successful effort to not roll her eyes again. Poor Chewy. He’s hot, with kind of a young Chris Pine vibe, but he’s also basically an idiot. He would’ve never gotten into Ridgemont if he weren’t legacy. If his parents hadn’t promised a new wing for the athletics building.

What makes Emma feel a little bit sorry for him is that he knows this. She can see it in the slightly apologetic way he turns in his assignments, and how he talks loudly about anything and everything he can think of (usually boobs) whenever he passes the construction site, with its sign that reads COMING SOON: BALLANTINE ATHLETICS FIELD HOUSE. “Don’t worry, Chewy,” she says. “You’ll understand in a sec. This is a descriptive essay, after all. It’s got a lot of visuals, which I understand boys are geared for.”

Chewy smiles and nods. “Visuals. Sweet.”

Emma looks down at her essay. It’s three pages long, typed in Garamond (her favorite font), and practically overflowing with specific, concrete details, just like Mr. Montgomery wanted.

She clears her throat again. Her hands shake a little. But she finds the courage to begin. The question is, will she be allowed to finish?

She’s written her essay exactly the way it should be, open to close: an attention-grabbing statement, followed by a walk-through of the elements she is proposing, and then an explanation of why. Emma is very aware that the shock value of her first line might have the power to knock Mr. Montgomery off his heels. She just needs him to stay that way until she gets to the all-important explanation.

“Four days from now, I will lock myself inside a Ridgemont Academy room, where I will set myself on fire,” Emma says evenly. “My essay today will describe exactly what will happen to me, and ultimately explain why I would choose to engage in a very public social suicide.”

Chewy’s mouth drops open.

Mr. Montgomery barks, “Emma, what, wait—”

But she ignores him completely. She imagines that she’s alone, reading out loud to herself, just like she did last night at 3:00 a.m. She practiced her performance a dozen times, ignoring the light snores that crept out from under Olivia’s CPAP mask—something that hasn’t made it into her Only- Fans stream yet.

No one can accuse Emma of not taking the assignment seriously. She just needs to make sure everyone understands exactly how serious she is.

“Fire needs fuel to burn,” Emma reads, “so my first step will be to douse myself in gasoline. While there are numerous other flammable liquids I could use, including paint thinner, lighter fluid, and nail polish remover, gasoline has a low flash point and burns extremely hot, so that’s what I’m going with. Also, it’s just kind of classic.”

She is dimly aware of the room getting noisier, of the sound of Mr. Montgomery pushing back his rolling desk chair. She keeps on reading. “Fire needs oxygen, too, so I’ll be wearing loose-fitting cotton clothing. Linen would work, but linen takes too much time to iron, and I want to look my best at my burning, although I’m not sure what filter works best with flames.” She smiles ever so slightly at her joke, but she doesn’t look up. She’s pretty sure no one will be smiling back. Instead, she imagines they are all gaping at one another, all of them asking with their eyes, Is she serious?

And, oh yes. She is.

“When I light my vintage Zippo (thanks, Grandpa) and hold the flame against my sleeve, my shirt will catch instantly. The fire will quickly spread across my chest and shoulders and down my legs. In a matter of seconds, blisters will erupt on my skin. My hair will ignite.”

In a crown of flames, she wanted to write, but then she crossed it out because it sounded too pretentious, which is exactly what she doesn’t want—to be one of them, lost in their own success story, not aware that the microcosm of their elite lives is built on a crumbling foundation.

She risks a glance at Chewy. The shock on his face makes him look even dumber than usual—whether that’s because he still hasn’t figured out what self-immolation is or he’s having to grapple with his first experience of being concerned for another human being, Emma’s not sure. Either way, he’s still hot.

“The pain will be the worst at the beginning,” Emma says, “before my nerves die. But I know that I won’t have to bear the pain too long. The smoke and fumes entering my respiratory tract will kill me quickly, if shock doesn’t do it first. Either way, I’ll die in a matter of minutes. Excruciating, agonizing minutes, sure—but minutes nonetheless.”

Spencer Jenkins goes, “That’s so sick!”

Out of the corner of her eye, she can see Mr. Montgomery hurrying toward her from the back of the room. “Emma,” he’s saying, “Emma, that’s enough!”

She raises her voice. Starts to read faster. “I won’t stop burning when I’d dead, though. The heat of the fire will make my skin shrink and split open. This will expose my subcutaneous fat, which is an excellent fuel source. The fat renders out—it liquefies, just like butter in a hot pan!—and then it’s absorbed into whatever surface I’m on.”

But now Mr. Montgomery is right in front of her, and he’s got his hands on her upper arms and he’s pushing her toward the door. Emma doesn’t try to resist, but she doesn’t stop talking either. Good thing she has the essay memorized. “This is known as the wick effect,” she calls over his shoulder. “Now, muscle is much harder to burn than fat, and bone is even harder than—”

But now he’s maneuvered her into the hallway and kicked the door shut behind them. He stares at her, his face white with shock. She can smell the cologne on his neck and the coffee on his breath. She has the wild, fleeting thought that Lizzie Grunwald would die of jealousy if she saw them right now, because Lizzie’s had a crush on Mr. Montgomery ever since the very first day of school.

Even with the door shut, Emma can hear the uproar she’s caused in the classroom. People asking if others think she means it, boys debating if her clothes will burn off before her skin blisters and if that’ll be sexy or not, and someone telling Rhaina that her thoughts about French horns still matter.

It’s exactly what Emma wanted. But the problem is that she’s not done. She has another page and a half of her essay to go—the part where she explains why.

“What the hell do you think you’re doing?” Mr. Montgomery hisses.

“I’m reading my essay, like you told me to,” she says calmly. “Aren’t you going to let me finish?”

“No, I am not!” Mr. Montgomery bristles. “How could you read something like that?”

“You said we could pick any topic we wanted,” she points out. “We just needed to include lots of specifics and details.”

“I said you should write about the beach!” he cries. “Or your pets!”

“You didn’t tell us things we couldn’t write about it.

And to be fair, I did give a warning.”

“How can you not understand how inappropriate this is?” His hands are tightening on her shoulders, his grip starting to hurt.

And while Emma can’t deny Lizzie Grunwald’s assertion that Mr. Montgomery is “bookishly handsome,” she also can’t get past the fact that she just announced her intention to set herself on fire, and he’s worried about the inappropriateness of the situation. Not, you know, her actual physical safety.

“Maybe if you had let me finish, you’d feel differently.” Emma tries to move toward the door again. She wants to get to the essay’s conclusion—that’s the entire point. She needs everyone to hear it. “If you understand my motivation—”

Mr. Montgomery grabs the essay from Emma. “You are not going to finish.” He practically spits his words in her face. “We are going to see the headmaster. Now.”

•••

Chapter 3

MR. MONTGOMERY’S LONG fingers keep their hold on Emma’s biceps as he guides her down the hall, out the door, and across the quad to the administration building.

With its gray stone facade softened by climbing ivy and purple wisteria, Pemberly Hall looks like an English manor house. Like the setting of a romance novel or a cozy mystery—the kind of books Emma’s mother used to devour when she thought no one was looking.

But there’s nothing romantic or mysterious about being marched to the headmaster’s office by a furious AP English teacher. They stop in front of the desk of the headmaster’s assistant, Fiona Dundy. On the wall behind her hangs a poster that reads EDISCERE. SCIRE. AGERE. VINCERE. It’s Ridgemont’s motto, and it means “Study. Know. Act. Win.”

Of course winning would be the ultimate goal of any Ridgemont graduate, and if Emma had been allowed to finish her essay, Mr. Montgomery would understand why her goal of self-immolation would ultimately be a win—maybe not for her, but for the world.

Ms. Dundy smiles brightly and says, “Oh, hello, sorry, Mr. Hastings is in a meeting.”

Her eyes slide to Emma, the sheen of her irises shifting into a slightly glazed look, the one that all the staff greet Emma with now. It is a careful look, one designed to measure the impact—or possibly repercussions—of speaking to Emma Blake.

But then her gaze shifts to Mr. Montgomery’s hand, still holding Emma’s upper arm tightly. Ms. Dundy’s mouth tightens, and Mr. Montgomery releases her.

“I don’t mean to be so brusque,” Mr. Montgomery says. “But I am very concerned about Emma.”

“Correction,” Emma speaks up. “He’s concerned about inappropriateness, not me. Not really.”

“You are inappropriate,” Montgomery snaps, spinning back to her.

“What you’re seeing now is not an example of how our staff typically speaks to students,” a deep voice says, and the English teacher goes pale.

Emma turns to see the headmaster.

Peregrine “Perry” Hastings is standing in the doorway of his office, flanked by a man and woman who—judging by their expensive clothes and hopeful expressions—have come to explore the possibility of their precious child attending Ridgemont Academy.

“I wouldn’t be overly concerned about how staff speak to students here,” Emma informs them. “Less than ten percent of applicants get into Ridgemont. But I’m sure you can find another overpriced school where free thought and expression are stifled.”

“Emma!” Mr. Hastings says sharply, then turns to the parents. “I’m so sorry. I apologize for the behavior of both Ms. Blake and Mr. Montgomery. Unfortunately, Emma has been going through some challenging life changes—”

Emma snorts. “Talk about a descriptive essay.”

As Mr. Hastings politely ushers Mom and Dad back into the reception area, Emma does have to give him some credit. He didn’t provide any sort of excuse for her English teacher’s behavior—only hers. A seed of hope blooms inside her chest. Maybe there’s a chance the headmaster will hear her out.

But Mr. Hastings’s politeness vanishes the instant the door shuts behind the visiting parents. “You two. Inside. Now.” He snaps his fingers in a way that must have been taught at an Ivy League school back in his day…but only to the male students, of course.

Inside his office, Emma drops into a vacated club chair. Mr. Montgomery remains standing, shifting from foot to foot in agitation and running his hand through his thick blondish hair. Mr. Hastings sits behind his mahogany desk, his stern gaze focused on Emma’s English teacher.

“What could possibly have you so agitated as to behave that way in front of prospective parents?”

“Basically, I did my homework really, really well,” Emma pipes up.

“Ms. Blake read an extremely inappropriate and upsetting essay to my class just now,” Mr. Montgomery says, shooting her a hard look. “I don’t know who to be worried about more—her or the rest of the students, who are in a state of shock.”

“Better than being in a state of slumber,” Emma mutters. “Which is where they were before I started reading.”

Mr. Hastings pushes his pale, bushy eyebrows together. There is far more hair on his forehead than above it. “What was the subject matter?”

“Why don’t you tell him, Emma?” Mr. Montgomery says.

“Why don’t you?” she counters.

Emma sees a vein pulsating at Mr. Montgomery’s temple. He’s sort of cute when he’s pissed. She can almost see why Lizzie’s so in love with him—either that or she herself only finds angry people attractive, which is totally possible given her concern for the lack of concern she sees everywhere else.

“Ms. Blake!” Mr. Hastings barks.

Emma blinks and returns her attention to the room. She crosses her long legs and tucks her hair behind her ears. She’s still mad that she didn’t get to finish reading her essay, but maybe she shouldn’t be so surprised. Sometimes someone puts a pin back into a grenade; sometimes a bomb gets caught right before it hits the ground.

She decides to be the picture of calm. “Mr. Montgomery assigned us a descriptive essay,” she says evenly. “He said that we should use lots of details and description. So I did.”

“What did you describe?”

“I described what happens to a person when they set themselves on fire.”

Mr. Hastings visibly flinches, the eyebrows that had been drawn together now going up in surprise. She’s not enjoying the men’s discomfort, but she’s not not enjoying it either.

“That isn’t even accurate!” Mr. Montgomery cries. “She said she was going to set herself on fire. Here, at Ridgemont Academy.”

The way he adds this particular detail—putting the emphasis on Ridgemont Academy instead of on her—makes Emma wonder if he’d be quite as upset if she’d declared her intention to do it off campus.

“Fine,” Emma concedes. “I did say that I was going to burn myself alive. The essay was well written, though, if I do say so myself.”

Unlike Mr. Montgomery, Mr. Hastings keeps his outward composure. “Emma, this is very distressing,” he says. “I’m shocked to hear this.”

“Are you, though?” Emma asks lightly. “I’m sure you’ve heard the rumors. ‘Emma Blake’s not herself lately.’ ‘Emma Blake’s been going downhill all semester.’ I’m not exactly bearing out our motto, am I? No big win at the end for this girl.” She points at herself with double thumbs, now definitely enjoying their discomfort.

Mr. Hastings and Mr. Montgomery make eye contact over Emma’s head. Emma imagines them communicating via some academic ESP.

Montgomery: She’s failing my class.

Hastings: She’s failing philosophy too. She quit the tennis team and the teen mentor program.

Montgomery: I never see her with any of her friends. It seems like she’s falling apart.

Hastings: Then we will tape her back together. We are Ridgemont Strong!

Mr. Hastings finally tears his gaze away from Mr. Montgomery and folds his hands together over his giant desk, and Emma braces herself for a barrage of meaningless words and empty promises.

“Let’s set aside, for a moment, the question of self-immolation,” Mr. Hastings says. “Let’s take a step back to reason and rationality. When someone like you—a straight-A student and a community leader—suddenly begins to disengage with school, we find ourselves asking why.”

Emma has been expecting anger, shock, some sort of sermon about how setting yourself on fire isn’t the Ridgemont way. But instead, Mr. Hastings is asking the question that no one else has—why?

“I kind of feel like it should be obvious,” she says. “I mean, you do know what happened in December? My ‘challenging life changes’? She puts her last words in air quotes. But Mr. Hastings keeps on going, still wearing an expression fresh out of a PowerPoint presentation titled “How to Connect with Emotionally Disturbed Minors.”

“When a student like you begins to fail classes,” he says, “and in her junior year no less, which is the most important year for college admissions, we really start to worry about her. We try to figure out how to help her. Emma, we are committed to supporting you. To seeing you through this difficult time. So I ask you, what can we do better?”

Once again, Hastings takes her by surprise. Sarcastically tossing his own words back didn’t ruffle him at all. Emma would almost buy it, if every word out of his mouth wasn’t corporatespeak.

“You can start by not pretending that your concern is me,” Emma says. “It’s Ridgemont’s reputation. What happens to the school’s statistics if one of its students—like me—starts bringing down the collective GPA?”

“That’s absolutely not true,” Mr. Hastings says. “We care about all of our students. We particularly care about you.”

“Mmmm…maybe it’s more like you care about Byron Blake’s daughter,” Emma says doubtfully. She picks at a snag on the sleeve of her sweater.

“I understand that it might be difficult to concentrate on schoolwork right now. I understand that there are… extenuating circumstances,” Mr. Hastings goes on.

“That’s one way to put it,” Emma says. The snag becomes a small hole.

“A death in the family is a terrible thing. And when it’s so recent—well, I understand that you are deep, deep in the grieving process.”

Anger floods Emma’s body, a chewed fingernail catching on the hole in her sweater. “You can’t even say the word,” she says. “I’m going through ‘challenging life changes,’ with ‘extenuating circumstances.’ If you can’t say the word, how can you possibly understand how I feel?”

Hastings closes his eyes. It looks to Emma like he’s trying to gather his strength. Then his eyes open with a snap, and he stares right at her. “Suicide,”he says, “is the tragedy of the greatest proportions.”

There. He said it. She didn’t think he would. Mr. Hastings keeps swinging at her pitches. And even though she made him do it, it still hits her like a gut punch.

“When people are grieving,” Mr. Hastings goes on, “they sometimes have very dark thoughts. But these must remain thoughts only. I cannot have you going around talking about setting yourself on fire, Emma Blake. There are other ways to express your sadness. And there are far better ways to process it. Do you understand me?”

What Emma now understands is that Mr. Hastings doesn’t think she’s serious about actually doing it. He thinks she’s having “thoughts only,” as a means to “express her sadness.”

She’s about to tell him how wrong he is when it occurs to her that his ignorance could be to her advantage. The less Mr. Hastings knows about her plans, the harder it will be for him to stop them.

•••

Chapter 4

SO SHE NODS and says, “Yes. I understand you. I understand that you’re trying to take away my right of free speech. Just like you did with the newspaper.”

She crosses her arms, pleased with her deft shift in topic. Now Mr. Hastings will have to address the fact that she was the editor in chief of the Ridgemont Trumpet for four whole months before they censored her right out of it, mostly because of the word he struggled so hard to enunciate a few moments earlier.

But it’s Mr. Montgomery who speaks first. “Emma, be reasonable,” he says. “We couldn’t have you writing upsetting things in the school paper.”

“You mean you can’t have me writing the truth,” Emma says.

“It’s very complicated,” Mr. Hastings says.

“No,” Emma says. “There’s nothing simpler than the truth. The problem is that no one ever wants to hear it.”

That’s why she wrote the essay for Montgomery’s class—to tell the truth. But they stopped her before she even got there. They got hung up on the gruesome details.

In a matter of seconds, blisters will erupt on my skin. My hair will ignite.

Okay, maybe she could’ve been a little more subtle. If she had, maybe she’d have gotten to the last line: You—all of you—are sleepwalking through global catastrophe. And with my death, I intend to wake you up.

“Emma,” Mr. Hastings says, “we’re worried about you. You are a brilliant student—a leader at Ridgemont. Please don’t let all that slip away.”

“Correction,” Emma says. “I used to be a leader at Ridgemont. After I realized that everyone here walks around with blinders on, I decided I didn’t want to lead sheep.” The leather creaks as Emma gets up from her chair. “I can’t believe my grades actually matter to you when the whole world is in crisis.”

Mr. Hastings blinks at her in surprise. “We aren’t talking about the world here, Emma—”

“Well, you should be! That’s my entire point.” Which they would know if they’d let her finish reading her essay.

“You’re trying to distract us from the problem at hand,” Mr. Hastings says, “which is your erratic and disturbing behavior.”

Emma barks out a laugh. “If my behavior is what you think is ‘the problem at hand,’ you haven’t read the news.”

Mr. Hastings reaches down and extracts that day’s New York Times from his recycling bin. He pushes the paper toward Emma so she can see the headlines: HUNDREDS FEARED DEAD AFTER MYANMAR FLOOD; THE HUMAN COST OF A BROKEN IMMIGRATION SYSTEM.

“I read the news every day,” he says quietly. “But my job is to care for the students under my charge. Which is why I’m putting you on academic probation and making you an appointment to speak to the school counselor.”

“And you’ll rewrite your essay,” Mr. Montgomery adds. “And it will be well crafted and appropriate, the way your essays were last semester. You are capable of it, and it will be good for you.”

“It’s a challenge you can rise to,” Mr. Hastings agrees. “However, I will add that I do want our students to find their work fulfilling. Like Mr. Montgomery, I believe an appropriate topic is necessary, and I also believe that you can find one that you care about. It seems that global issues matter to you. Why not write about climate change? Or our failing health care system?”

Emma wants to scream. Everyone’s so desperate for her to be the happy, active girl she used to be. She’s been the freaking Ridgemont poster child, getting straight A’s in her classes, leading student clubs, dominating on the soccer field and the tennis court. Everyone misses that girl terribly, and they’d do anything to get her back.

Hell, even Emma misses her. But she can’t get her back. That girl is gone forever. That girl died in December too. “People already write about those things,” Emma says quietly, tapping her fingernail on his copy of the New York Times.“No one is listening to scientists, to experts, to doctors and lawyers and people with a string of degrees after their names. No one is going to listen to a privileged white girl unless she does something drastic. I already rose to your challenges, and I accomplished nothing that actually mattered. I don’t want to be your poster child anymore.”

Mr. Hastings leans across his desk so his face is barely a foot away from hers. She can see the individual pores on his nose.

“But do you want to set yourself on fire?” he asks.

“Of course she doesn’t!” Mr. Montgomery exclaims. “She just wanted to shock all of us!”

Emma’s seen what Mr. Montgomery drives: a Honda Civic. His suit jackets are off-the-rack, not tailor-made. He probably eats the heels of his bread loaves, drinks Walmart coffee, and drives to school every day believing that none of his rich students have any real problems. But we’re living on the same planet, and the outlook is not good.

Mr. Hastings, however, is still holding her gaze, still waiting for an answer to whether or not she actually wants to set herself on fire…and he looks like he might actually care about her response.

Emma swivels away from Mr. Hastings and offers Mr. Montgomery a half smile. “It was a good presentation, admit it,” she tells him. “Everyone was paying attention. You can’t say that about anyone else’s essay. You could barely keep your eyes open during Rhaina’s exploration of the joys of a French horn.”

Mr. Montgomery stiffens. He looks like he’s being strangled by his tie. “I won’t tell you it was good.”

Emma lifts an eyebrow, mildly surprised. Sure, she’s failing English now, and most of her other classes. But she used to get A’s in her sleep. “Okay, then,” she says. “What grade would you give it?”

She tries to make it sound like she doesn’t actually care all that much, but there’s still a little bit of pride deep down, a tiny place inside of her that wants to know she could climb out of this hole she’s dug for herself—if she really wanted to.

“Setting aside the issue of the topic and its utter inappropriateness for AP English,” Mr. Montgomery says, “I’d give you a C plus. Maybe a B minus.”

“That’s it?” Emma is truly surprised.

Old Emma would have spent ten minutes before class drafting essays, spouting clichés and well-worn phrases that she knew adults liked and would reward with A’s. But she put real effort into today’s essay, revealed in those pages her heart, soul, and core beliefs.

“The sentences were elegant,” Mr. Montgomery goes on. “The details were awful but powerful. However, I asked for an essay that described your personal experience. Your essay came from research.”

Dammit. The man is not wrong.

It’s ironic, though, isn’t it? In another few days, she actually would be able to write about burning from personal experience. Except for the whole problem of being dead.

“I understand your point,” she says calmly. “I’ll try to do better next time.”

But if Emma gets her way—and she usually does—there won’t be a next time.